Not Just a Drink: Wassail

“Wassail, wassail, all over the town

Our toast it is white and our ale it is brown

Our bowl it is made of the white maple tree

With the wassailing bowl we’ll drink to thee”

— Gloucestershire Wassail Carol

When you read the lyrics aloud to this drinking song (or hear the tune), you can almost feel that cup of hot alcohol in your hand as you drunkenly sway to and fro, singing at the top of your lungs around the Christmas tree. The drink, wassail, conjures images of caroling revelers dressed in boughs of holly and fir with wooden crocks full of good cheer in a Bacchus-type parade through city streets. It’s nostalgia wrapped in a warm blanket of cider, mulled wine, nutmeg and floating orange slices. A celebratory holiday gathering around a highly decorative punch bowl. But, wassail has a muddled heritage. Is it warm booze? An action verb? A hearty salutation? A song? Yes. It’s all of these things, and it includes a storied family tree rooted in tradition and branching out in nearly every direction for over a millennium.

I salute thee…Waes hael!

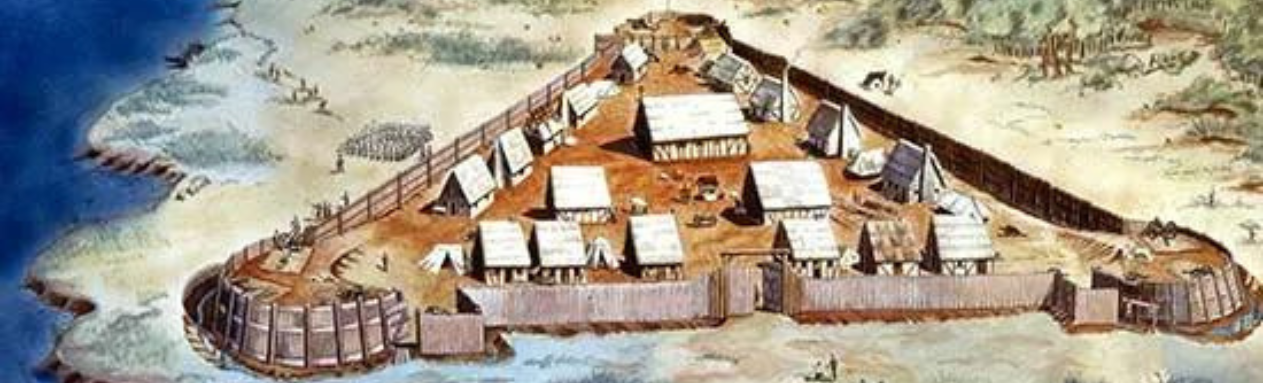

First, let’s rewind to a castle in 5th-century Britain, where Rowena — the beautiful daughter of a Saxon leader — seduces an incredibly inebriated King Vortigern with a goblet of spiced wine, giving the first recorded toast in history to his good health by crying out, “Waes hael!” Taken by her beauty, he immediately beds then weds the girl after ordering her to drink of the same cup and exclaiming, “Drinc hael!” — “drink, and good health!” This moment in British history becomes the foundation on which one thousand years of wassail tradition spring forth and is said to be the first documented “toast” in history. Seems legit, right?

Whether we are to believe a drunken king wearing wine goggles is charmed into bed, then marriage by a potion-bearing, Saxon babe — thus inadvertently setting the course of the Western world’s drinking culture — is neither here nor there. The point is, it’s a great story. One of many attributed to the history and lore which seem to surround wassail. No one really knows what was in that goblet. Was it spiced wine? Mead? Ale? It doesn’t matter. Wassail was not a drink that night. It was simply a salutation — a toast among drinking buddies celebrating the good health of their friend, the king. Whatever the case, the salute stuck. The word as we know it today, “wassail,” first appears in the 8th century poem “Beowulf”. In the poem, it is again not a drink, but a salute to its warriors.

“Forlorn he looks on the lodge of his son,

wine-hall waste and wind-swept chambers

reft of revel. The rider sleepeth,

the hero, far-hidden; no harp resounds,

in courts no wassail, as once was heard.”

Get wassailed

“I’ve always liked the fact that wassail produced a verb — wassailing, which suggests roots in social activity — something arising out of the dark, northern days of the holiday season. I’ve heard people talk about going cocktailing, but that doesn’t have the same ring.”

Long after Vortigern and Rowena’s intoxicating meeting, wassail continued to dominate English drinking culture in one form or another. The act of “wassailing” dates back to pre-Christian times when farmers living in England’s southeastern apple-growing region would gather in the mid-winter chill in the orchards collectively shouting while pouring cider onto their trees to ward off evil spirits. By wassailing their crops in the winter, it was said to ensure a healthy crop in the spring. As Christianity began to spread, this ritual evolved further into singing and drinking to the health of next season’s crops on Twelfth Night; the last night of the traditional Christmas season. It seemed only appropriate to attach the celebration of Christ’s birth and his visit from three wisemen with the hope for a good yield in the orchards in the coming year. It also assured them not being burned as heretics under the ever-watchful eye of the Church.

In some regions of medieval Britain, wassail involved a large gathering of tenants at the manor house where the master, channeling Rowena, would hold up a bowl of steaming spiced wine or ale and shout, “Wassail!” with the crowd replying, “Drink hail!” before devolving into Christmas revelry. Yet in other regions, wassailing took on a slightly sinister tone with drunken crowds gathering outside feudal lords’ homes while bowls of ale flowed, singing loudly and not dispersing until they received Christmas treats. Hence the line in We Wish You a Merry Christmas, “Now give us a figgy pudding. We won’t go until we get some.” You can imagine the fear of the manors’ inhabitants watching a fire, backlit crowd of drunken idiots demanding food growing larger and louder by the minute. That’s enough to make anyone relent to mob rule.

In the 14th century, someone decided to morph the old story of King Vortigern and Rowena, their boozy salute, and the passing of the loving cup yet again. This time, the act of door-to-door drinking took a cue from the simple act of saluting and celebrating to a healthy, happy new year. Crowds of carolers would visit neighbors rather than their masters with a large wassailing bowl filled with a spiced punch of mulled wine or ale, nutmeg and sugar. People would then dip toasted bread into the mixture to soak up the flavor and share in the merriment. This band of intoxicated carousers unwittingly created our modern word to “toast” by simply floating a few croutons in a bowl of ale. But it was from here, the act of wassailing and its drink would forever merge, forming one of cocktail’s most enduring partnerships.

Wassail, wassail!

By the Renaissance, wassailing had a firm foothold in England’s Christmas traditions. The drunken band of rabble-rousers banging on doors begging for figgy pudding was now simply spreading good cheer door-to-door in the village while singing Christmas carols with a punch bowl of sweetened, spiced ale. But it was during the 17th century the liquid inside the bowl finally started to take center stage in the merry ritual of Christmas and its now 500-year love affair with apples. The rich punch-like mixture called “Lambswool” was considered the wassail drink of choice for the Christmas punch bowl of the day. It contained warm ale or mulled wine, sugar, nutmeg, eggs, toasts, and “crabs” — steaming, roasted crab apples dropped still-hot into the warm punch, bursting upon impact and making a hissing sound as the mixture frothed and bubbled. The crabs gave the punch a tart sweetness while adding a bit of drama. It is from Lambswool that what we know as the traditional Christmas wassail drink was birthed.

From wassail to nog to toddy

What started as most likely mead or spiced wine sweetened with honey has gone through many transformations throughout the centuries. Wassail evolved from a hot punch-like beverage of mulled wine spiced with nutmeg and raisins to keep the winter chill at bay for loitering merrymakers to its modern Christmas cousin, the cider concoction containing wine, bobbed apples, and sliced oranges and in some households, to an even richer, cream-based punch containing sherry, crusts of bread or sweet cakes, and even eggs.

As the punch matured, mixtures of madeira, sherry, or brandy began to appear alongside the the traditional ale or cider, becoming a modern, more complex split based punch. When settlers began arriving in America, “wassailing” had become nothing more than a celebratory gathering at home with friends during Christmas with a cider-based punch spiked with rum. An ocean now separated the old and new. Wassail’s American transformation continued as generations grew further from their English roots, streamlining the creamy Lambswool-based punches into egg nog or the cider-rum mixtures into a wassail-for-one with the whiskey-forward hot toddy. It is these drinks we now most associate with our modern holiday traditions as the punch bowl of yore gathers dust on the shelf in the China cabinet.

The carousing traditions of wassail may have gotten lost in its own convoluted history, but the drink that emerged from the lore continues to play a small role in the nostalgia that is Christmas in the Western world. Many still gather around the punch bowl, sometimes singing carols, often happily sipping a cider-based, spiced concoction which today may or may not contain alcohol. Even the vessel has modernized, with wassail being kept warm for party-goers’ convenience in the crock pot; always at the ready for ladling into a punch cup.

Wassail is indeed both a noun and a verb. Mostly it is a salutatory celebration of a long year as you gather with those you cherish and raise a glass of good cheer to toast to a healthy, happy new year and enduring friendships. For wassail is, first and foremost, a salute.

So, we say to you, TOTCF readers, whatever you believe, “Wassail! Drink hail!”

Now to Drink:

Wassailing

Wassailing is a very ancient custom that is rarely done today. The word ‘wassail’ comes from the Anglo-Saxon phrase ‘waes hael’, which means ‘good health’. Originally, the wassail was a drink made of mulled ale, curdled cream, roasted apples, eggs, cloves, ginger, nutmeg and sugar. It was served from huge bowls, often made of silver or pewter.

The Wassail drink mixture was sometimes called ‘Lamb’s Wool’ because of the pulp of the roasted apples looked all frothy and a bit like Lambs Wool! Here is a recipe for wassail.

Wassailing was traditionally done on New Year’s Eve and Twelfth Night, but some rich people drank Wassail on all the 12 days of Christmas!

One legend about how Wassailing was created, says that a beautiful Saxon maiden named Rowena presented Prince Vortigen with a bowl of wine while toasting him with the words ‘waes hael’.

Over the centuries, a great deal of ceremony developed around the custom of drinking wassail. The bowl was carried into a room with a great fanfare, a traditional carol about the drink was sung, and finally, the steaming hot beverage was served.

The person offering the drink would say “wassail” (good health) and the recipient would reply “drinkhail” (drink good health). From this it developed into another way of saying Merry Christmas to each other!

One of the most popular Wassailing Carols went like this:

Here we come a-wassailing

Among the leaves so green,

Here we come a-wassailing,

So fair to be seen:

Love and joy come to you,

And to you your wassail too,

And God bless you and send you,

A happy New Year,

And God send you,

A happy new year.

Jesus College, in Oxford University, has a Wassail bowl, that is covered with silver. It can hold 10 gallons of drink!

Wassailing Apple Trees

In parts of England (such as Somerset and Sussex) where apples are grown, especially for cider, Wassailing still takes place on Twelfth Night (or sometimes New Year’s Eve or even Christmas Eve). People go into apple orchards and then sing songs, make loud noises and dance around to scare off any evil spirits and also to ‘wake up’ the trees so they will give a good crop! The Wassail is also sometimes poured over the roots of the trees to ‘feed’ them.

It’s also common to place toast which has been soaked in beer or cider into the boughs of the trees to feed and thank the trees for giving apples. That’s where the term to ‘toast’ someone with a drink comes from!

In parts of South Wales in the United Kingdom, there is the tradition of the ‘Mari Lwyd’ wassailing horse.

Mulled Wine

Mulled wine is an alcoholic drink made by warming red wine and adding other flavors and spices including cinnamon, cloves, star anise and ginger. Sometimes fruit such as oranges and lemons are also added. It’s normally served hot/warm but can be also be served cold. Sometimes non-alcoholic wine is used.

The earliest records of warmed wine with spices come from the Romans. They could well have taken this warming drink around Europe. The first ‘modern’ description of a warm wine drink is in a medieval English cookery book from 1390.

It became more popular during the Victorian period as Wassail was drunk less less with the demise of Twelfth Night parties.

Different variations of mulled wine include ‘Smoking Bishop’ which is made with port, red wine and lemons or oranges, with the oranges often being studded with cloves. Smoking Bishop was mentioned at the end of A Christmas Carol, by Charles Dickens in 1843, where the reformed Scrooge arranges to talk to Bob Cratchit over a ‘Christmas bowl of smoking bishop’.

There are other ‘ecclesiastics’ including ‘Smoking Archbishop’ made with claret; ‘Smoking Beadle’ made with ginger wine and raisins; ‘Smoking Cardinal; made with Champagne and ‘Smoking Pope’ made with burgundy.

In German speaking countries, mulled wine is known as Glühwein and there’s also Feuerzangenbowle, where a block of rum-soaked sugarloaf is set alit and sits over and drips into the mulled wine. Mulled wine is known by other names in different countries including glögg, vin chaud, vino caliente, vin brulé and bisschopswijn.

Why Do We Drink That? The History of Wassail

The word “wassail” has a long, tradition-rich history.

Dating back to the seventh century, wassail has meant everything from “to dance in celebration,” to “a warm, spicy beverage drunk as a hope for good health.”

And historically, during the Anglo-Saxon period between 410-1066 AD, pagans seemed to do both: wassailing through the orchards singing and pouring wine on the crops as a ritual for an abundant harvest!

Today, we know wassail as a popular holiday cocktail. Something warm and spiced we drink as a celebration of the season.

But why do we drink that?

Grab a glass and lean in as we tell you the story behind the revelrous cocktail that has inspired some pretty epic Game of Thrones-esque parties throughout the ages.

What Is Wassail?

A hot beverage made with wine, beer, or cider, spices, citrus, and apples, wassail is typically served during the holiday season in a big bowl.

Deriving from the Old Norse greeting “Ves Heill,” similar to the Old English expression “be in good health” (Merriam-Webster), wassail is known as a sort of tonic.

Hardly surprising given that wassail’s ingredients are rich in potassium, magnesium, and vitamin C.

Plus, a tipple of alcohol never hurts the soul either, right?

But it’s not just wassail’s ingredients that surprise and delight.

Wassail Throughout the Ages

Throughout over fourteen centuries, Wassail has given rise to several remarkably original traditions, customs, and recipes.

Seventh Century: The oldest recorded mention of wassail appears in one of the oldest known poems in the English language—an Old English poem called Beowulf.

“The rider sleepeth, the hero, far-hidden; no harp resounds, in the courts no wassail, as once was heard,” reads the line in Beowulf.

Thirteenth Century: The term “wassail bowl,” a steaming bowl of ale and fortified wine, first appears.

Similarly, during this time the name “toast,” which we associate with raising our glasses in celebration, originates from the practice of medieval partygoers dipping bread and cakes into a huge bowl of ale. Which could or could not have been wassail!

Seventeenth Century: At this time, people start taking the warm wassail bowl from door to door as a festive offering of happiness and peace.

The term “wassailing” evolves over time to suggest alcoholic celebration in a more general sense.

Nineteenth Century: The puritans bring the tradition of wassail bowls to America, sparking the creation of other large bowl beverages, like eggnog and the hot toddy.

Late Twentieth to Early Twenty-First Century: Present-day revelers continue to drink wassail around the holidays, singing its praises (literally) in a classic holiday song simply called “The Wassail Song.”

With lyrics that wish good health, love, joy, and happiness in the new year, the now-traditional English Christmas carol has become a favorite to sing during the holiday season.

For instance, like the March sisters in the 1994 adaptation of “Little Women.”

This holiday, might be the time for you to start your own wassailing tradition.

How to Make Wassail

For a drink so rich in history, wassail is surprisingly easy to make.

You just need a few key seasonal fruits, spices, and of course spirits.

Although if you want to get fancy, this warm beverage has a lot of garnish options, like brandy-soaked apple slices or frothy egg-white topping with nutmeg. Feel free to be as festive as you please and make your wassail your own.

The best part is that the wassail will still be as enjoyable without alcohol—just omit the brandy.

Here’s a homemade recipe for the holiday or anytime beverage.

Ingredients:

Serves 8-10 cups

2 quarts apple cider

2 cups orange juice

½ cup brandy

1 cup pineapple juice

5 whole cloves

5 cinnamon sticks

5 star anise

1/2 cup cranberries

1 orange, sliced

1 apple, sliced

Nutmeg

Instructions:

1) Add the apple cider, orange juice, and pineapple juice to a big pot over low heat.

2) Once the liquid begins to steam, add the apple slices, cranberries, orange slices, cinnamon sticks, star anise, cloves, and nutmeg.

3) Simmer for at least an hour to infuse the liquid.

4) Ladle only the warm liquid into a mug, garnish with a cinnamon stick, and a fresh apple slice.

To get the full effect, don’t forget to toast and say, “Cheers to your health!”

Facebook

Facebook

X

X

Pinterest

Pinterest

Copy Link

Copy Link