Spooky, Creepy, Morbid, Yes Christmas Cards!

Some of the Earliest Christmas Cards Were Morbid and Creepy. Santa kidnapping children and murderous mice were par for the course in the Victorian-era Christmas card tradition.

In the 19th century, before festive Christmas cards became the norm, Victorians put a darkly humorous and twisted spin on their seasonal greetings. Some of the more popular subjects included anthropomorphic frogs, bloodthirsty snowmen and dead birds.

“May yours be a joyful Christmas,” reads one card from the late 1800s, along with an illustration of a dead robin. Another card shows an elderly couple laughing maniacally as they lean out a second-story window and dump water onto a group of carolers below. “Wishing you a jolly Christmas,” it says beneath the image.

Morality and a strict code of social conduct embodied the time period of Queen Victoria’s reign (1837-1901), but the Victorians still had their fair share of questionable practices. They thought nothing of posing with the dead or robbing graves and selling the bodies. Their holiday customs evolved with just as much curiosity. Clowns, insects and even the Devil himself had a place in early holiday fanfare.

“In the 19th century, the iconography of Christmas had not been fully developed as it is now,” says Penne Restad, a lecturer in American history at the University of Texas in Austin and the author of Christmas in America.

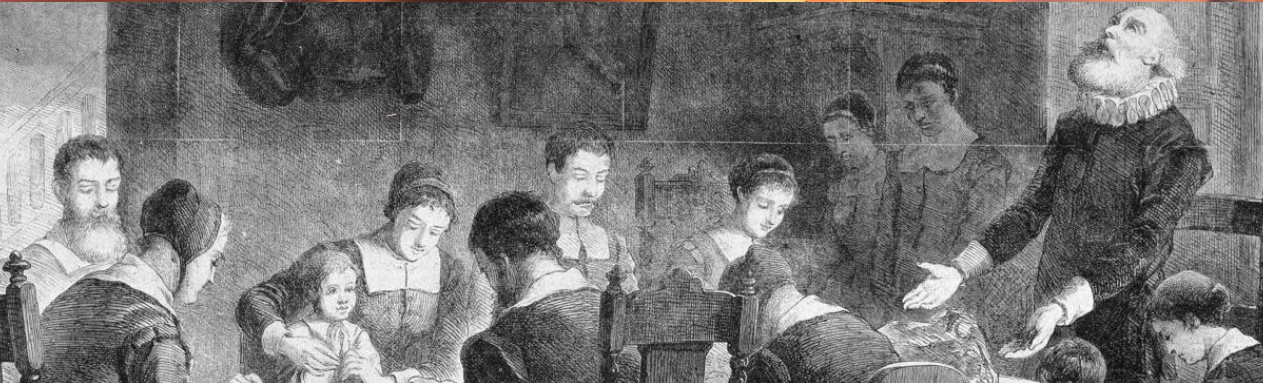

The first Christmas card, circa 1843.

Christmas didn’t gain momentum until the mid-1800s. In 1843, the same year that English author Charles Dickens created A Christmas Carol, prominent English educator and society member, Sir Henry Cole, commissioned the first Christmas card. Even with an impressive print run of 1,000 cards (of which 21 exist today), full-fledged manufacturing remained only a sideline to the more established trade in playing cards, notepaper and envelopes, needle-box and linen labels and valentines, explains Samantha Bradbeer, archivist and historian for Hallmark Cards, Inc. It took several decades for the exchange of holiday greetings to catch on, both in England and the United States.

“Several factors coincided to produce a broad acceptance of greeting cards as a popular commodity,” says Bradbeer, including a higher literacy rate and new consumerism stemming from increasing levels of discretionary income. But postal reform and advances in printing technologies were the two factors that really pushed Christmas cards into the mainstream.

The Postage Act of 1839 helped regulate British postage rates and democratize mail delivery. A year later, with the passage of the Uniform Penny Post law, anyone in England could send something in the mail for just one penny. Then, in October 1870, right before the holiday season, the British government introduced the halfpenny, making mail service affordable for nearly all levels of society. Standardized rates and delivery soon followed in America.

At the same time, wood cuts and other cumbersome printing processes gave way to the mass production of images. The first mass printing of Christmas cards occurred in the 1860s. By 1870, when printing could be done for as little as a few pennies per dozen, hundreds of European card manufacturers were producing cards to sell at home and to the American public. German immigrant Louis Prang is credited with popularizing the Christmas card in the United States through his Boston lithography business.

As the popularity of Christmas cards grew, Victorians demanded more novelty. “By 1885, unique and even bizarre cards with silk fringe, glittered attachments and mechanical movements were popular, but the more common Christmas card motifs related to flora and fauna, seasonal vignettes and landscapes,”.

Among the bizarre were a large collection of dark and outlandish designs. An army of black ants is shown attacking an army of red ants on one holiday greeting with the caption, “The compliments of the season,” printed on a tiny flag. Sullen and brooding children, random lobsters and Christmas pudding with human elements made frequent appearances on Christmas cards printed in the late 1800s and early 1900s.

But why did Victorians exchange such eccentric holiday cards, and what do they mean?

“I think it’s important to understand that ‘festive’ cards as we know them now are very much a 20th-century phenomena,” says Katie Brown, assistant curator of social history at York Castle Museum. According to Brown, although some of the history is lost, designs were made to serve as conversation pieces as much as they were made to celebrate the season. Many Victorian Christmas cards became parlor art or people added them to their scrapbook collections.

Greeting cards, in general, are linked socially, economically and politically to the culture, period and place of their origin and use. “Sentiments and designs that may seem unusual today were often considered signs of good fortune, while others poked fun at superstitions,” .

Folk customs influenced the design of many Victorian Christmas cards. In British folklore, for example, robins and wrens are considered sacred species. John Grossman, author of Christmas Curiosities: Old, Dark and Forgotten Christmas, writes that images of these dead birds on Christmas cards may have been “bound to elicit Victorian sympathy and may reference common stories of poor children freezing to death at Christmas.”

“I believe the cultural interest in fairies, secret places and strange creatures that developed, maybe beginning with seances, elves and so on, in the Victorian era may have something to do with some of the fantastical Christmas cards,” says historians .

St. Nicholas Teams Up With the Devil

A German postcard reading “Gruss vom Krampus,” meaning “Greetings from Krampus.”

An English legend popular during the Victorian era said that St. Nicholas recruited the Devil to help with his deliveries. Together, they determined which children had been naughty or nice. The Devil, who appeared under various guises, kidnapped the disobedient kids and beat them with a stick. Santa is the creepy antihero on a variety of Victorian-era holiday cards, where he can be seen peeking through windows and spying on children. The Devil is disguised as Krampus on some, making off on sleds and in automobiles with the children deemed naughty.

Today, despite the rise of electronic communication and social media, billions of Christmas cards are bought and exchanged around the world each year.

“As artifacts of popular culture revealing graphic, literary and social trends, they provide both visual pleasure and important historic information,” says historians, even when that information is symbolized by dead birds.

History of the card

A prominent educator and patron of the arts, Henry Cole travelled in the elite, social circles of early Victorian England, and had the misfortune of having too many friends.

During the holiday season of 1843, those friends were causing Cole much anxiety.

The problem were their letters: An old custom in England, the Christmas and New Year’s letter had received a new impetus with the recent expansion of the British postal system and the introduction of the “Penny Post,” allowing the sender to send a letter or card anywhere in the country by affixing a penny stamp to the correspondence.

Now, everybody was sending letters. Sir Cole—best remembered today as the founder of the Victoria and Albert Museum in London—was an enthusiastic supporter of the new postal system, and he enjoyed being the 1840s equivalent of an A-Lister, but he was a busy man. As he watched the stacks of unanswered correspondence he fretted over what to do. “In Victorian England, it was considered impolite not to answer mail,”. “He had to figure out a way to respond to all of these people.”

Cole hit on an ingenious idea. He approached an artist friend, J.C. Horsley, and asked him to design an idea that Cole had sketched out in his mind. Cole then took Horsley’s illustration—a triptych showing a family at table celebrating the holiday flanked by images of people helping the poor—and had a thousand copies made by a London printer. The image was printed on a piece of stiff cardboard 5 1/8 x 3 1/4 inches in size. At the top of each was the salutation, “TO:_____” allowing Cole to personalize his responses, which included the generic greeting “A Merry Christmas and A Happy New Year To You.”

Bingo, It was the first Christmas card.

Unlike many holiday traditions—can anyone really say who sent the first Christmas fruitcake?—we have a generally agreed upon name and date for the beginning of this one. But as with today’s brouhahas about Starbucks cups or “Happy Holidays” greetings, it was not without controversy. In their image of the family celebrating, Cole and Horsley had included several young children enjoying what appear to be glasses of wine along with their older siblings and parents. “At the time there was a big temperance movement in England,” Collins says. “So there were some that thought he was encouraging underage drinking.”

The criticism was not enough to blunt what some in Cole’s circle immediately recognized as a good way to save time. Within a few years, several other prominent Victorians had simply copied his and Horsley’s creation and were sending them out at Christmas.

While Cole and Horsley get the credit for the first, it took several decades for the Christmas card to really catch on, both in Great Britain and the United States. Once it did, it became an integral part of our holiday celebrations—even as the definition of “the holidays” became more expansive, and now includes not just Christmas and New Year’s, but Hanukkah, Kwanzaa and the Winter Solstice.

Louis Prang, a Prussian immigrant with a print shop near Boston, is credited with creating the first Christmas card originating in the United States in 1875. It was very different from Cole and Horsley’s of 30 years prior, in that it didn’t even contain a Christmas or holiday image. The card was a painting of a flower, and it read “Merry Christmas.” This more artistic, subtle approach would categorize this first generation of American Christmas cards. “They were vivid, beautiful reproductions,” says Collins. “There were very few nativity scenes or depictions of holiday celebrations. You were typically looking at animals, nature, scenes that could have taken place in October or February.”

Appreciation of the quality and the artistry of the cards grew in the late 1800s, spurred in part by competitions organized by card publishers, with cash prizes offered for the best designs. People soon collected Christmas cards like they would butterflies or coins, and the new crop each season were reviewed in newspapers, like books or films today.

In 1894, prominent British arts writer Gleeson White devoted an entire issue of his influential magazine, The Studio, to a study of Christmas cards. While he found the varied designs interesting, he was not impressed by the written sentiments. “It’s obvious that for the sake of their literature no collection would be worth making,” he sniffed. (White’s comments are included as part of an online exhibit of Victorian Christmas cards from Indiana University’s Lilly Library)

“In the manufacture of Victorian Christmas cards,” wrote George Buday in his 1968 book, The History of the Christmas Card, “we witness the emergence of a form of popular art, accommodated to the transitory conditions of society and its production methods.”

The modern Christmas card industry arguably began in 1915, when a Kansas City-based fledgling postcard printing company started by Joyce Hall, later to be joined by his brothers Rollie and William, published its first holiday card. The Hall Brothers company (which, a decade later, change its name to Hallmark), soon adapted a new format for the cards—4 inches wide, 6 inches high, folded once, and inserted in an envelope.

“They discovered that people didn’t have enough room to write everything they wanted to say on a post card,” says Steve Doyal, vice president of public affairs for Hallmark, “but they didn’t want to write a whole letter.”

In this new “book” format—which remains the industry standard—colorful Christmas cards with red-suited Santas and brilliant stars of Bethlehem, and cheerful, if soon clichéd, messages inside, became enormously popular in the 1930s-1950s. As hunger for cards grew, Hallmark and its competitors reached out for new ideas to sell them. Commissioning famous artists to design them was one way: Hence, the creation of cards by Salvador Dali, Grandma Moses and Norman Rockwell, who designed a series of Christmas cards for Hallmark (the Rockwell cards are still reprinted every few years). (The Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art has a fascinating collection of more personal Christmas cards sent by artists including Alexander Calder.)

Jacqueline Kennedy painted two Christmas card designs for Hallmark in 1963. The designs, including Glad Tidings (featured) and the Journey of the Magi, were to be sold as a benefit for the Kennedy Center. Courtesy of the Hallmark Archives, Hallmark Cards, Inc., Kansas City, Mo.

Between 1948 and 1957, Norman Rockwell created 32 Christmas card designs, including Santa Looking at Two Sleeping Children (1952) for Hallmark. Courtesy of the Hallmark Archives, Hallmark Cards, Inc., Kansas City, Mo.

The most popular Christmas card of all time, however, is a simple one. It’s an image of three cherubic angels, two of whom are bowed in prayer. The third peers out from the card with big, baby blue eyes, her halo slightly askew.

“God bless you, keep you and love you…at Christmastime and always,” reads the sentiment. First published in 1977, that card—still part of Hallmark’s collection—has sold 34 million copies.

The introduction, 53 years ago, of the first Christmas stamp by the U.S. Post Office perhaps speaks even more powerfully to the popularity of the Christmas card. It depicted a wreath, two candles and had the words “Christmas, 1962.” According to the Post Office, the department ordered the printing of 350 million of these 4-cent, green and white stamps. However, says Daniel Piazza, chief curator of philately for the Smithsonian’s National Postal Museum, “they underestimated the demand and ended up having to do a special printing.”

But there was a problem.

“They didn’t have enough of the right size paper,” Piazza says. Hence, the first printing of the new Christmas stamps came in sheets of 100. The second printing was in sheets of 90. (Although they are not rare, Piazza adds, the second printing-sheets of these stamps are collectibles today).

Still, thanks to the round the clock efforts by the Bureau of Engraving and Printing, a total of one billion copies of the 1962 Christmas stamp were printed and distributed by the end of the year.

Today, much of the innovation in Christmas cards is found in smaller, niche publishers whose work is found in gift shops and paper stores. “These smaller publishers are bringing in a lot of new ideas,” says Peter Doherty, executive director of the Greeting Card Association, a Washington, D.C.-based trade group representing the card publishers. “You have elaborate pop up cards, video cards, audio cards, cards segmented to various audiences.”

The sentiments, too, are different than the stock greetings of the past. “It’s not always the touchy-feely, ‘to you and yours on this festive, glorious occasion’ kind of prose,” says Doherty. “Those cards are still out there, but the newer publishers are writing in a language that is speaking to a younger generation.”

Henry Cole’s first card was a convenient way for him to speak to his many friends and associates without having to draft long, personalized responses to each. Yet, there are also accounts of Cole selling at least some of the cards for a shilling apiece at his art gallery in London, possibly for charity. Maybe Sir Cole was not only a pioneer of the Christmas card, but prescient in his recognition of another aspect of our celebration of Christmas.

Facebook

Facebook

X

X

Pinterest

Pinterest

Copy Link

Copy Link